Figure 1. The JSON post format

図1 投稿時に用いるJSONフォーマット

Documents are CouchDB’s central data structure. To best understand and use CouchDB, you need to think in documents. This chapter walks you though the lifecycle of designing and saving a document. We’ll follow up by reading documents and aggregating and querying them with views. In the next section, you’ll see how CouchDB can also transform documents into other formats.

ドキュメントはCouchDBにとってなくてはならないデータ構造です。CouchDBを使いこなすためには、ドキュメントとしてどんなデータを扱うかを考えるところから始めるとよいと思います。この章ではドキュメントのデザインから保存にいたるまでのライフサイクルを取り扱います。その過程で viewによるドキュメントの照会、集計や問い合わせについても解説します。次の節から、ドキュメントを様々なフォーマットに変換する機能も紹介していきます。

Documents are self-contained units of data. You might have heard the term record to describe something similar. Your data is usually made up of small native types such as integers and strings. Documents are the first level of abstraction over these native types. They provide some structure and logically group the primitive data. The height of a person might be encoded as an integer (176), but this integer is usually part of a larger structure that contains a label ("height": 176) and related data ({"name":"Chris", "height": 176}).

ドキュメントはいくつかのデータで構成されるまとまりのようなものです。あなたはそれと似たようなものを指すrecordという用語を聞いたことがあるかも知れません。データ自体は数値型、文字列型といったネイティブな型によって構成されていますが、CouchDBのドキュメントという単位はこうしたネイティブな型から飛躍した、抽象的なデータ型として取り扱うことを想定した仕組みとして実装されています。たとえば、人の身長は (176)という数字で表現できますが、("height": 176)といったようにラベルを付与したほうがわかりやすくなります。そして、({"name":"Chris", "height": 176})と関連する他の項目とまとめたほうがさらにわかりやすくなるでしょう。

How many data items you put into your documents depends on your application and a bit on how you want to use views (later), but generally, a document roughly corresponds to an object instance in your programming language. Are you running an online shop? You will have items and sales and comments for your items. They all make good candidates for objects and, subsequently, documents.

構造が異なる複数のドキュメントを使用するアプリケーションであっても、viewを使う処理を多用したとした場合であっても、CouchDBのドキュメントはプログラミング言語が提供しているオブジェクトインスタンスと常に整合性を取ることができます。オンラインショップを構築したいのであれば、商品、売り上げ、コメントといった単位でデータをドキュメントとして設計すればよいでしょう。いずれも、オブジェクトとドキュメントとして取り扱うのによい単位です。

Documents differ subtly from garden-variety objects in that they usually have authors and CRUD operations (create, read, update, delete). Document-based software (like the word processors and spreadsheets of yore) builds its storage model around saving documents so that authors get back what they created. Similarly, in a CouchDB application you may find yourself giving greater leeway to the presentation layer. If, instead of adding timestamps to your data in a controller, you allow the user to control them, you get draft status and the ability to publish articles in the future for free (by viewing published documents using an endkey of now).

ドキュメントはそれぞれ構造や内容が異なるものですが、著者といった項目やCRUDによる操作など、共通している部分もあります。ドキュメント指向のソフトウェア(たとえば、ワープロソフトや表計算ソフトなど)はドキュメントを保存する機能が必要です。CouchDBではドキュメントの保存すべき構造をより柔軟にユーザー自身で定義することができます。自動的にタイムスタンプを付与するような処理がない代わりに、ユーザーはドキュメントの内容全てを決めることができます。ドラフト版のドキュメントを残しておくこともできますし、任意のタイミングでドキュメントを公開できます。(endkeyにnowを指定してviewを使えば、新しく発行されたドキュメントの確認はいつでもできますし)

Validation functions are available so that you don’t have to worry about bad data causing errors in your system. Often in document-based software, the client application edits and manipulates the data, saving it back. As long as you give the user the document she asked you to save, she’ll be happy.

バリデーション関数により、あなたのシステム上で正しくないデータがエラーを引き起こす懸念は軽減されるはずです。多くのドキュメント指向のソフトウェアでは、クライアント側にあるアプリケーションがデータを編集・操作、保存することになります。ユーザーの要求に応じてドキュメントを保存できる仕組みを提供すれば、きっと喜んでくれるでしょう。

Say your users can comment on the item (“lovely book”); you have the option to store the comments as an array, on the item document. This makes it trivial to find the item’s comments, but, as they say, “it doesn’t scale.” A popular item could have tens of comments, or even hundreds or more.

ユーザーがある商品に「lovely book」といったようにコメントを付ける機能も提供することができます。商品のドキュメント内に配列として複数のコメントを格納するオプションを指定することができます。商品のコメントを探すのは些細な問題ではありませんが、スケールするのが難しくなります。人気のある商品は数百、またはそれ以上にコメントが書き込まれることを想定しておかねばなりません。

Instead of storing a list on the item document, in this case it may be better to model comments into a collection of documents. There are patterns for accessing collections, which CouchDB makes easy. You likely want to show only 10 or 20 at a time and provide previous and next links. By handling comments as individual entities, you can group them with views. A group could be the entire collection or slices of 10 or 20, sorted by the item they apply to so that it’s easy to grab the set you need.

商品のドキュメントにコメントに対してコメントのリストを付与する場合は、コメントを別のドキュメントとして切り出すほうがよいでしょう。CouchDBでドキュメントの構造を設計するためのよいパターンのひとつです。たとえば、10件や20件といった単位で表示させることや、前のコメントや次のコメントといったようなリンクを作ることができるかもしれません。コメントの捌き方はviewを利用すれば簡単に実現することができます。一度に全てを表示させることもできますし、表示する数を調整することもできます。あるキーを基準にして整列して表示させることもできます。

A rule of thumb: break up into documents everything that you will be handling separately in your application. Items are single, and comments are single, but you don’t need to break them into smaller pieces. Views are a convenient way to group your documents in meaningful ways.

これまでの経験より:アプリケーションで管理するドキュメントはあまり細かくない粒度で切り分けるのがコツです。これまでの解説で出てきたような、商品やコメントといった単位で十分です。それ以上細かくする必要はありません。あとはビューを利用してドキュメントの集合を管理するのがよいやり方です。

Let’s go through building our example application to show you in practice how to work with documents.

サンプルアプリケーションの作成を通じて、実際のドキュメントの取り扱い方をお見せします。

The first step in designing any application (once you know what the program is for and have the user interaction nailed down) is deciding on the format it will use to represent and store data. Our example blog is written in JavaScript. A few lines back we said documents roughly represent your data objects. In this case, there is a an exact correspondence. CouchDB borrowed the JSON data format from JavaScript; this allows us to use documents directly as native objects when programming. This is really convenient and leads to fewer problems down the road (if you ever worked with an ORM system, you might know what we are hinting at).

アプリケーションを設計するにあたって、最初にやるべきことはデータの書式を決めることです(もちろん、プログラムの目的やユーザーの用例を理解したうえでのことです)。例のブログアプリケーションはJavaScriptで書かれています。先ほど述べたとおり、ドキュメントは粒度が粗めのデータオブジェクトとして表現されます。CouchDBではJavaScriptによるJSON形式によるドキュメントの構造を採用しています。これにより、プログラミング時にドキュメントをネイティブなオブジェクトとして直接操作することができるのです。これはとても便利で、書かなければならないコードも少なくてすみます(もしあなたが、ORMシステムに関する仕事をしているなら、私たちが何をヒントにしているのか気が付いたかもしれません)。

Let’s draft a JSON format for blog posts. We know we’ll need each post to have an author, a title, and a body. We know we’d like to use document IDs to find documents so that URLs are search engine–friendly, and we’d also like to list them by creation date.

ブログの投稿記事を表現するためにJSON形式でドキュメントを表現してみましょう。各投稿ごとに著者、タイトル、記事内容といった項目が必要になります。ドキュメントを探すときにドキュメントのIDを指定するかもしれません。IDが含まれたURLは検索エンジンにとって親和性が高いものになるでしょう。また、投稿日付の順に一覧表示することを要求される場合もあるでしょう。

It should be pretty straightforward to see how JSON works. Curly braces ({}) wrap objects, and objects are key/value lists. Keys are strings that are wrapped in double quotes (""). Finally, a value is a string, an integer, an object, or an array ([]). Keys and values are separated by a colon (:), and multiple keys and values by comma (,). That’s it. For a complete description of the JSON format, see Appendix E, JSON Primer.

JSON形式はとてもシンプルです。キーと値のリストをブレース({})で囲みます。キーは文字列として、ダブルクォート("")で囲んで書きます。値の種類には文字列、数値、オブジェクト、配列([])があります。キーと値は間にコロン(:)を入れるようにします。キーと値のペアを列挙するときはカンマ(,)で区切ります。詳細は付録E「JSON入門」をご覧ください。

Figure 1, “The JSON post format” shows a document that meets our requirements. The cool thing is we just made it up on the spot. We didn’t go and define a schema, and we didn’t define how things should look. We just created a document with whatever we needed. Now, requirements for objects change all the time during the development of an application. Coming up with a different document that meets new, evolved needs is just as easy.

例の図1「投稿時に用いるJSONフォーマット」にあるドキュメントは要件を反映させた内容になっています。任意のタイミングでドキュメントを定義し、使うことができるところがとても優れています。スキーマを定義したり、後々のことを想定した設計はしていません。必要に応じてその場でドキュメントを作成しているのです。アプリケーションを開発する期間、データの要件が絶え間なく変化していくような場合は、JSON形式でデータをドキュメントとして定義すると開発がはかどります。

Figure 1. The JSON post format

図1 投稿時に用いるJSONフォーマット

Do I really look like a guy with a plan? You know what I am? I’m a dog chasing cars. I wouldn’t know what to do with one if I caught it. You know, I just do things. The mob has plans, the cops have plans, Gordon’s got plans. You know, they’re schemers. Schemers trying to control their little worlds. I’m not a schemer. I try to show the schemers how pathetic their attempts to control things really are.

私は計画的な人間に見えますか?おそらく私は車を追う犬のようなものです。車を捕まえた後に何をすべきかなど私にはわかりません。つまり、単に目先のことをひたすらにこなすだけなのです。マフィアや警官、そしてゴードンもまた計画を基準に行動します。彼らは陰謀家です。陰謀家はわずかな言葉であらゆるものをコントロールしようと試みます。しかし、私は陰謀家ではありません。彼ら陰謀家の試みが実に哀れであるかをお見せしましょう。

—The Joker, The Dark Knight

—ジョーカー、ダークナイトより

Let’s examine the document in a little more detail. The first two members (_id and _rev) are for CouchDB’s housekeeping and act as identification for a particular instance of a document. _id is easy: if I store something in CouchDB, it creates the _id and returns it to me. I can use the _id to build the URL where I can get my something back.

ドキュメントの詳細について説明します。最初のふたつ(_idと_rev)はCouchDBが管理している項目で、ドキュメントの特定のインスタンスを一意に識別するために使用します。_idはわかりやすいですね。CouchDB上にドキュメントを作成すると、自動的に_idを返してくれます。_idはドキュメントの在り処を示すURLに用いられます。

Your document’s _id defines the URL the document can be found under. Say you have a database movies. All documents can be found somewhere under the URL /movies, but where exactly?

ドキュメントの_idはそのままドキュメントのURLの一部になります。映画(movies)に関するデータベースがあるとしましょう。すべてのドキュメントは/moviesの配下にあります。それぞれの映画を指定するにはどうしたらいいでしょうか?

If you store a document with the _id Jabberwocky ({"_id":"Jabberwocky"}) into your movies database, it will be available under the URL /movies/Jabberwocky. So if you send a GET request to /movies/Jabberwocky, you will get back the JSON that makes up your document ({"_id":"Jabberwocky"}).

moviesデータベースに_idがJabberwocky({"_id":"Jabberwocky"})であるドキュメントを保存した場合、URLは/movies/Jabberwockyとなります。/movies/Jabberwockyに対してGETメソッドを送信すれば、ドキュメントがJSON形式({"_id":"Jabberwocky"})で返ってきます。

The _rev (or revision ID) describes a version of a document. Each change creates a new document version (that again is self-contained) and updates the _rev. This becomes useful because, when saving a document, you must provide an up-to-date _rev so that CouchDB knows you’ve been working against the latest document version.

_rev(またはリビジョンID)はドキュメントのバージョンを表します。ドキュメントの更新は内部的には新しいバージョンのドキュメントを作成していることになります。そして、_revを更新するのです。_revの更新は自動的に行われるため、開発者が世代管理を意識してプログラミングする必要がありません。

We touched on this in Chapter 2, Eventual Consistency. The revision ID acts as a gatekeeper for writes to a document in CouchDB’s MVCC system. A document is a shared resource; many clients can read and write them at the same time. To make sure two writing clients don’t step on each other’s feet, each client must provide what it believes is the latest revision ID of a document along with the proposed changes. If the on-disk revision ID matches the provided _rev, CouchDB will accept the change. If it doesn’t, the update will be rejected. The client should read the latest version, integrate the changes, and try saving again.

2章「結果整合性」でも、リビジョンには触れました。リビジョンIDはCouchDBのMVCCシステムにおいて、ドキュメントへの書き込み処理を制御する役割を持ちます。ドキュメントは共有され、複数の利用者からの参照と更新を同時に受け付けます。二つの書き込み処理が競合しない状態を維持するために、各クライアントはドキュメントについて変更時のリビジョンIDを最新版として保持しています。ディスク上にあるリビジョンIDと書き込み処理が指定した_revが一致したとき、CouchDBは書き込み処理を受け入れます。そうでない場合、更新は破棄されます。クライアントはドキュメントの最新版を読み込むべきであり、何度でも変更の保存は試みられて然るべきです。

This mechanism ensures two things: a client can only overwrite a version it knows, and it can’t trip over changes made by other clients. This works without CouchDB having to manage explicit locks on any document. This ensures that no client has to wait for another client to complete any work. Updates are serialized, so CouchDB will never attempt to write documents faster than your disk can spin, and it also means that two mutually conflicting writes can’t be written at the same time.

この仕組みにより、二つのことが保証されます。クライアントは自身が読み込んだバージョンのドキュメントに対する更新のみを正確に実行することが可能となります。また、他のクライアントによりこちらの更新内容が上書きされることもありません。更新処理時にCouchDBはドキュメントに対して明示的なロックをかけません。クライアントは他のクライアントの更新処理が終わるのを待たずに済みます。更新処理は順次実行されます。そのため、CouchDBはディスクの回転速度よりも速い書き込み処理を要求することはありません。つまり、同じタイミングで発生した二つの書き込み処理は同時に書き込まれることがないことを意味しています。

Now that you thoroughly understand the role of _id and _rev on a document, let’s look at everything else we’re storing.

_idと_revについては理解できたと思います。他のところも見ていきましょう。

{

"_id":"Hello-Sofa",

"_rev":"2-2143609722",

"type":"post",

The first thing is the type of the document. Note that this is an application-level parameter, not anything particular to CouchDB. The type is just an arbitrarily named key/value pair as far as CouchDB is concerned. For us, as we’re adding blog posts to Sofa, it has a little deeper meaning. Sofa uses the type field to determine which validations to apply. It can then rely on documents of that type being valid in the views and the user interface. This removes the need to check for every field and nested JSON value before using it. This is purely by convention, and you can make up your own or infer the type of a document by its structure (“has an array with three elements”—a.k.a. duck typing). We just thought this was easy to follow and hope you agree.

まずはドキュメントの種類についてです。これはアプリケーションで任意に設定しているパラメーターであって、CouchDB特有のものではありません。CouchDBからすれば、単なるキーと値のペアにすぎませんが、アプリケーションのSofaからすれば重要な意味を持っています。Sofaはtypeという項目をどのバリデーション機能を適用するかを決めるときに使用します。ビューやユーザーインターフェースの動作はドキュメントの種類に大きく依存します。ドキュメントの種類とバリデーションを紐付けることでアプリケーションロジックの中で各項目のチェックを実行する必要がなくなります。これは純粋に慣習によるものなので、あなたはドキュメントの種類を自分で考えたり、(「3つの要素を持つ配列を持っているものは」というようないわゆるダックタイピングで)ドキュメントの構造から種類を推論することもできます。私達はこの慣習は従いやすいものだと考えていて、あなたもこれに同意してくれると思います。

"author":"jchris", "title":"Hello Sofa",

The author and title fields are set when the post is created. The title field can be changed, but the author field is locked by the validation function for security. Only the author may edit the post.

authorとtitleは記事が投稿されたときに設定されます。titleが変更された場合でもあっても、authorはセキュリティを考慮したバリデーション関数により、値がロックされます。authorは記事を投稿する初回のみ設定が可能な項目です。

"tags":["example","blog post","json"],

Sofa’s tag system just stores them as an array on the document. This kind of denormalization is a particularly good fit for CouchDB.

Sofaのタグデータはドキュメント上で配列として保存されます。配列を用いてデータをグルーピングするような方法はCouchDBと相性がとてもよいです。

"format":"markdown", "body":"some markdown text", "html":"<p>the html text</p>",

Blog posts are composed in the Markdown HTML format to make them easy to author. The Markdown format as typed by the user is stored in the body field. Before the blog post is saved, Sofa converts it to HTML in the client’s browser. There is an interface for previewing the Markdown conversion, so you can be sure it will display as you like.

ブログの投稿はMarkdown記法で書きます。記述内容はbodyという項目に格納します。記事が保存されると、Sofaは記事をHTMLに変換してブラウザに表示します。プレビュー機能も備えているので、書いている途中でも適宜HTMLの結果を確認することができます。

"created_at":"2009/05/25 06:10:40 +0000" }

The created_at field is used to order blog posts in the Atom feed and on the HTML index page.

created_atは日付の項目で、記事を表示させる順番やAtomによる配信の順番の基準になります。

The first page we need to build in order to get one of these blog entries into our post is the interface for creating and editing posts.

最初に必要なのは、記事を書いて投稿するための画面です。

Editing is more complex than just rendering posts for visitors to read, but that means once you’ve read this chapter, you’ll have seen most of the techniques we touch on in the other chapters.

編集機能は単に記事をレンダリングして表示するよりも複雑ではありますが、本書を読み進めていくうちに必要なテクニックはおよそ身に付けることができると思います。

The first thing to look at is the show function used to render the HTML page. If you haven’t already, read Chapter 8, Show Functions to learn about the details of the API. We’ll just look at this code in the context of Sofa, so you can see how it all fits together.

まずはHTMLページをレンダリングするshow関数を見てみましょう。show関数のことがよくわからない方は8章「ショウ機能」にあるAPIの解説を先にご覧ください。Sofaのコードで以下のような記述があると思います。

function(doc, req) {

// !json templates.edit

// !json blog

// !code vendor/couchapp/path.js

// !code vendor/couchapp/template.js

Sofa’s edit page show function is very straightforward. In the previous section, we showed the important templates and libraries we’ll use. The important line is the !json macro, which loads the edit.html template from the templates directory. These macros are run by CouchApp, as Sofa is being deployed to CouchDB. For more information about the macros, see Chapter 13, Showing Documents in Custom Formats.

Sofaの編集画面を表示するためのshow関数は実にシンプルです。前のセクションで、私達はここで使用する重要なテンプレートとライブラリを紹介しました。重要な行は!jsonマクロの行で、これがtemplatesディレクトリからedit.htmlテンプレートを読み込みます。インポートしたマクロの部分はCouchDBへデプロイするときにCouchAppによってshow関数内に展開されます。マクロに関する詳しい情報は13章「任意の書式によるドキュメントの表示」をご覧ください。

// we only show html

return template(templates.edit, {

doc : doc,

docid : toJSON((doc && doc._id) || null),

blog : blog,

assets : assetPath(),

index : listPath('index','recent-posts',{descending:true,limit:8})

});

}

The rest of the function is simple. We’re just rendering the HTML template with data culled from the document. In the case where the document does not yet exist, we make sure to set the docid to null. This allows us to use the same template both for creating new blog posts as well as editing existing ones.

残りの関数はシンプルです。ドキュメントからデータを抜き出して、HTMLのテンプレートでレンダリングをしているにすぎません。存在しないドキュメントが指定された場合はdocidにnullを設定して空のドキュメントを返すようにしています。この工夫により、記事の表示と新規作成とで同じテンプレートの共有を実現しています。

The only missing piece of this puzzle is the HTML that it takes to save a document like this.

残るはドキュメントの保存に関する部分です。

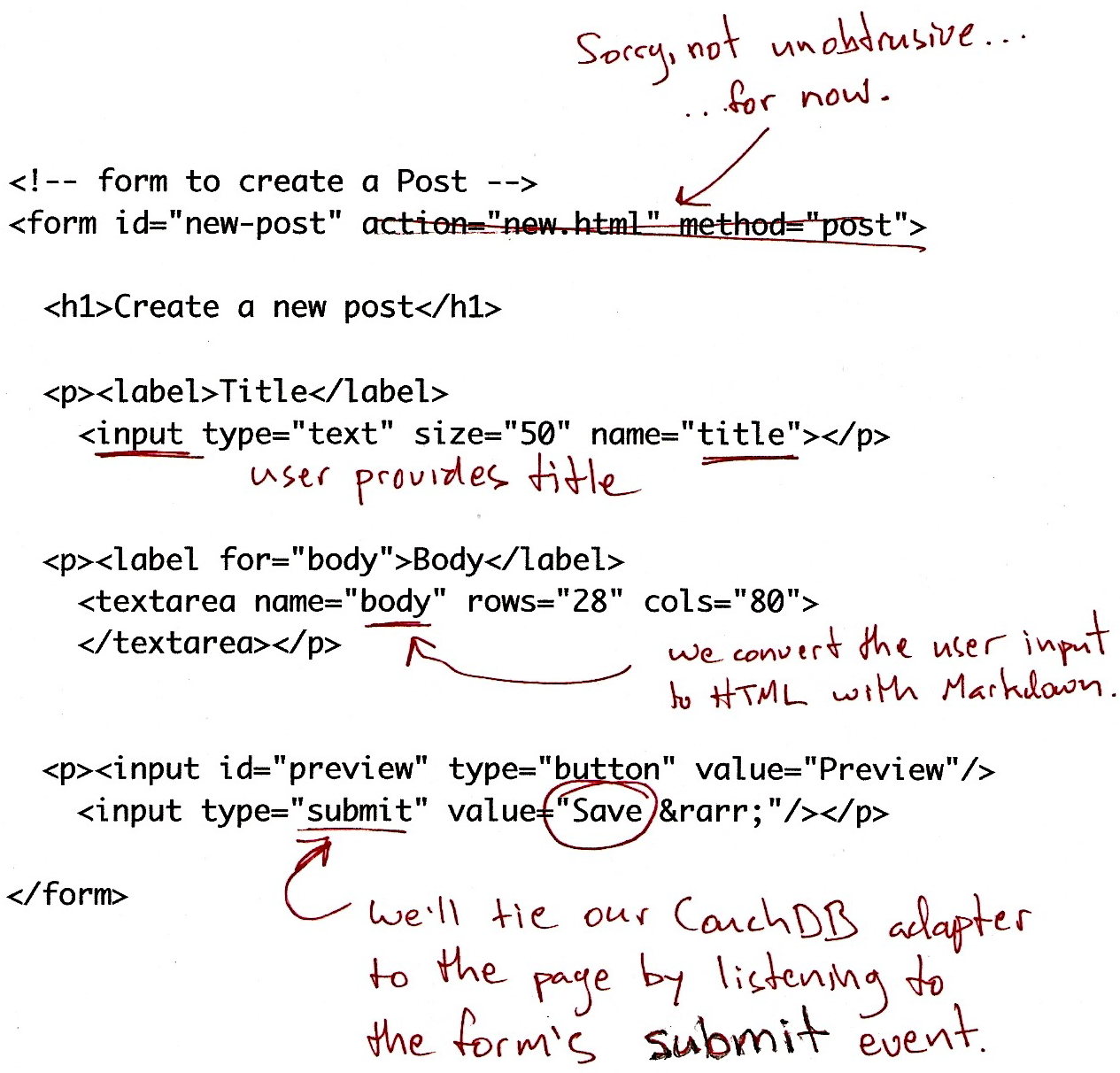

In your browser, visit http://127.0.0.1:5984/blog/_design/sofa/_show/edit and, using your text editor, open the source file templates/edit.html (or view source in your browser). Everything is ready to go; all we have to do is wire up CouchDB using in-page JavaScript. See Figure 2, “HTML listing for edit.html”.

ブラウザでhttp://127.0.0.1:5984/blog/_design/sofa/_show/editにアクセスし、テキストエディタでtemplates/edit.htmlというファイルを開いてみてください(またはブラウザからソースコードを表示させてみてください)。必要な処理の全てをJavaScriptのロジックとしてCouchDBへ実装しています。図2 「edit.htmlを表示させるためのHTML」を見てください。

Just like any web application, the important part of the HTML is the form for accepting edits. The edit form captures a few basic data items: the post title, the body (in Markdown format), and any tags the author would like to apply.

多くのWebアプリケーションにとってフォームを利用した編集機能の提供は欠かせない要件です。サンプルの編集画面を見ると基本的な構成になっているのがわかります。記事のタイトル、記事の内容(Markdownの書式で書くことができる)、そして記事に対する任意のタグを付与できるようになっています。

<!-- form to create a Post -->

<form id="new-post" action="new.html" method="post">

<h1>Create a new post</h1>

<p><label>Title</label>

<input type="text" size="50" name="title"></p>

<p><label for="body">Body</label>

<textarea name="body" rows="28" cols="80">

</textarea></p>

<p><input id="preview" type="button" value="Preview"/>

<input type="submit" value="Save →"/></p>

</form>

We start with just a raw HTML document, containing a normal HTML form. We use JavaScript to convert user input into a JSON document and save it to CouchDB. In the spirit of focusing on CouchDB, we won’t dwell on the JavaScript here. It’s a combination of Sofa-specific application code, CouchApp’s JavaScript helpers, and jQuery for interface elements. The basic story is that it watches for the user to click “Save,” and then applies some callbacks to the document before sending it to CouchDB.

フォームを備えた通常のHTMLドキュメントを用意するところから始めました。JavaScriptは入力情報をJSON形式のドキュメントに変換し、CouchDBへ保存するのに使用します。CouchDBにスポットを当てたいので、ここではJavaScriptの詳細については書きません。 Sofaは固有のアプリケーションロジックとCouchAppによるJavaScriptのヘルパー関数、jQueryによるDOMの操作といった三つの要素が結びついて出来上がっています。ユーザーの「Save」ボタンを押す操作を監視して、ドキュメントをCouchDBへ送る前に複数のコールバック関数へメッセージを送ることで、実際には様々な処理が実行されています。

Figure 2. HTML listing for edit.html

図2 edit.htmlを表示させるためのHTML

The JavaScript that drives blog post creation and editing centers around the HTML form from Figure 2, “HTML listing for edit.html”. The CouchApp jQuery plug-in provides some abstraction, so we don’t have to concern ourselves with the details of how the form is converted to a JSON document when the user hits the submit button. $.CouchApp also ensures that the user is logged in and makes her information available to the application. See Figure 3, “JavaScript callbacks for edit.html”.

ブログの記事の新規作成と編集を行うJavaScriptは図2「edit.htmlを表示させるためのHTMLのHTMLフォームに集まっています。CouchApp jQueryプラグインがいくらか抽象化してくれるので、ユーザーが送信ボタンを押したとき、どのようにしてフォームがJSONドキュメントに変換されるのかということの詳細に私達が関わる必要はありません。また、$.CouchAppはユーザーがログインしていて、その人の情報をアプリケーションが利用できることを確実にします。図3「edit.htmlで使うJavaScriptのコールバック関数」を見てください。

$.CouchApp(function(app) {

app.loggedInNow(function(login) {

The first thing we do is ask the CouchApp library to make sure the user is logged in. Assuming the answer is yes, we’ll proceed to set up the page as an editor. This means we apply a JavaScript event handler to the form and specify callbacks we’d like to run on the document, both when it is loaded and when it saved.

ユーザーがログインしたときに、CouchAppのライブラリーを参照するか確認しておきましょう。エディターでedit.htmlを開いて見てみると、任意の処理を書き込めることがわかると思います。つまりフォーム内にJavaScriptによるイベントハンドラーを定義し、ドキュメントが読み込まれた時や保存された時といった特定にタイミングで、コールバック関数を実行できることを意味しています。

Figure 3. JavaScript callbacks for edit.html

図3 edit.htmlで使うJavaScriptのコールバック関数

// w00t, we're logged in (according to the cookie)

$("#header").prepend('<span id="login">'+login+'</span>');

// setup CouchApp document/form system, adding app-specific callbacks

var B = new Blog(app);

Now that we know the user is logged in, we can render his username at the top of the page. The variable B is just a shortcut to some of the Sofa-specific blog rendering code. It contains methods for converting blog post bodies from Markdown to HTML, as well as a few other odds and ends. We pulled these functions into blog.js so we could keep them out of the way of main code.

ユーザーがログインしたら、トップページにユーザーの名前が表示されます。変数Bはブログ記事をレンダリングするために用意された特定のソースコードへのショートカットになっています。その中にはMarkdown記法で書かれたものをHTMLに変換する処理も含まれています。こうした関数はblog.js内に定義してあるため、アプリケーションのメインのコードはきれいな状態を維持しています。

var postForm = app.docForm("form#new-post", {

id : <%= docid %>,

fields : ["title", "body", "tags"],

template : {

type : "post",

format : "markdown",

author : login

},

CouchApp’s app.docForm() helper is a function to set up and maintain a correspondence between a CouchDB document and an HTML form. Let’s look at the first three arguments passed to it by Sofa. The id argument tells docForm() where to save the document. This can be null in the case of a new document. We set fields to an array of form elements that will correspond directly to JSON fields in the CouchDB document. Finally, the template argument is given a JavaScript object that will be used as the starting point, in the case of a new document. In this case, we ensure that the document has a type equal to “post,” and that the default format is Markdown. We also set the author to be the login name of the current user.

app.docForm()はCouchDBのドキュメントとHTMLフォームの整合性を取るために必要な関数です。Sofaで利用している最初の3つの引数を見てみましょう。idという引数はドキュメントを保存するところをdocForm()に伝えるために使用します。新しいドキュメントを作る場合はidがnullになります。fieldsはCouchDBのドキュメントとJSON形式の各項目とを紐付けるときに利用するフォームの属性を配列として格納するために使います。最後のtemplateという引数はドキュメントが新しく作成されたタイミングなどで、JavaScriptのオブジェクトを初期化するときに使われます。この場合はドキュメントの種類が「post」であることを保証し、デフォルトのフォーマットがMarkdown記法でることを設定しています。また、ログイン時の名前を画面に表示する名前として設定しています。

onLoad : function(doc) {

if (doc._id) {

B.editing(doc._id);

$('h1').html('Editing <a href="../post/'+doc._id+'">'+doc._id+'</a>');

$('#preview').before('<input type="button" id="delete"

value="Delete Post"/> ');

$("#delete").click(function() {

postForm.deleteDoc({

success: function(resp) {

$("h1").text("Deleted "+resp.id);

$('form#new-post input').attr('disabled', true);

}

});

return false;

});

}

$('label[for=body]').append(' <em>with '+(doc.format||'html')+'</em>');

The onLoad callback is run when the document is loaded from CouchDB. It is useful for decorating the document before passing it to the form, or for setting up other user interface elements. In this case, we check to see if the document already has an ID. If it does, that means it’s been saved, so we create a button for deleting it and set up the callback to the delete function. It may look like a lot of code, but it’s pretty standard for Ajax applications. If there is one criticism to make of this section, it’s that the logic for creating the delete button could be moved to the blog.js file so we can keep more user-interface details out of the main flow.

onLoadのコールバック関数はドキュメントが CouchDBに読み込まれたときに実行されます。フォームに表示させる前や他のユーザーインターフェースに変換するときに、ドキュメントを加工する処理を挟み込むのに使えます。関数の冒頭で、IDがすでに振られているかを確認しているのがわかります。IDがあることは、すでにドキュメントが保存されていることを意味するため、ドキュメントを削除するボタンを追加し、削除を実行するコールバック関数を定義しています。あまりないパターンかもしれませんが、Ajaxのアプリケーションではよくやる方法です。気持ちが悪いという方には、ボタンを動的に追加する処理はblog.js内に書くという方法もあります。そうすると、アプリケーションロジックとユーザーインターフェースのロジックをより明確に切り離すことができるようになります。

},

beforeSave : function(doc) {

doc.html = B.formatBody(doc.body, doc.format);

if (!doc.created_at) {

doc.created_at = new Date();

}

if (!doc.slug) {

doc.slug = app.slugifyString(doc.title);

doc._id = doc.slug;

}

if(doc.tags) {

doc.tags = doc.tags.split(",");

for(var idx in doc.tags) {

doc.tags[idx] = $.trim(doc.tags[idx]);

}

}

},

The beforeSave() callback to docForm is run after the user clicks the submit button. In Sofa’s case, it manages setting the blog post’s timestamp, transforming the title into an acceptable document ID (for prettier URLs), and processing the document tags from a string into an array. It also runs the Markdown-to-HTML conversion in the browser so that once the document is saved, the rest of the application has direct access to the HTML.

docFormへのコールバック関数であるbeforeSave()関数はユーザーがsubmitボタンを押したときに実行されます。タイムスタンプを設定したり、記事のタイトルと可能な限り同じドキュメントIDを生成したり、文字列からタグを切り分けて配列へ格納したりします。Markdown記法で書かれたドキュメントがHTMLへ変換されるのもこのタイミングになります。そのため、一度ドキュメントが保存されれば、以降の処理は全てHTMLに対して行えばよいことになります。

success : function(resp) {

$("#saved").text("Saved _rev: "+resp.rev).fadeIn(500).fadeOut(3000);

B.editing(resp.id);

}

});

The last callback we use in Sofa is the success callback. It is fired when the document is successfully saved. In our case, we use it to flash a message to the user that lets her know she’s succeeded, as well as to add a link to the blog post so that when you create a blog post for the first time, you can click through to see its permalink page.

Sofaで使う最後のコールバック関数はsuccessコールバック関数です。ここでは、保存に成功したことを伝えるメッセージを一時的に表示させ、記事へのリンクを追加しています。記事を投稿すれば、パーマネントリンクをたどって記事へアクセスすることができます。

That’s it for the docForm() callbacks.

以上がdocForm()のコールバック関数です。

$("#preview").click(function() {

var doc = postForm.localDoc();

var html = B.formatBody(doc.body, doc.format);

$('#show-preview').html(html);

// scroll down

$('body').scrollTo('#show-preview', {duration: 500});

});

Sofa has a function to preview blog posts before saving them. Since this doesn’t affect how the document is saved, the code that watches for events from the “preview” button is not applied within the docForm() callbacks.

記事を保存する前に記事のプレビューを表示して内容を確認することができます。この機能はドキュメントの保存とは関係ありません。previewボタンが押されたときに実行されます。docForm()のコールバック関数とは関係なく動作します。

}, function() {

app.go('<%= assets %>/account.html#'+document.location);

});

});

The last bit of code here is triggered when the user is not logged in. All it does is redirect him to the account page so that he can log in and try editing again.

残りはユーザーがログインしていないときに実行される関数です。アカウントを認証するページにリダイレクトさせ、ログイン後に再び記事の編集をしてもらう仕組みです。

Hopefully, you can see how the previous code will send a JSON document to CouchDB when the user clicks save. That’s great for creating a user interface, but it does nothing to protect the database from unwanted updates. This is where validation functions come into play. With a proper validation function, even a determined hacker cannot get unwanted documents into your database. Let’s look at how Sofa’s works. For more on validation functions, see Chapter 7, Validation Functions.

これまでに紹介してきたコードを見れば、保存ボタンを押したときにどのようにしてJSON形式のドキュメントがCouchDBに格納されるのかがわかると思います。しかし、それだけではデータベースに対する望ましくない更新を防ぐことはできません。バリデーション関数が必要になるでしょう。バリデーション関数を正しく実装しておけば、クラッカーによる不正行為も未然に防ぐことができます。ここではSofaの実装例を見てみましょう。バリデーションに関する詳細を見たい場合は7章「バリデーション機能」をご覧ください。

function (newDoc, oldDoc, userCtx) {

// !code lib/validate.js

This line imports a library from Sofa that makes the rest of the function much more readable. It is just a wrapper around the basic ability to mark requests as either forbidden or unauthorized. In this chapter, we’ve concentrated on the business logic of the validation function. Just be aware that unless you use Sofa’s validate.js, you’ll need to work with the more primitive logic that the library abstracts.

最初の行は後の関数をより読みやすくするためにSofaからライブラリを読み込みます。これはリクエストにforbiddenやunauthorizedというような印を付ける基本的な能力の単なるラッパーです。この章では、私達はバリデーション関数のビジネスロジックに集中します。Sofaのvaildate.jsを使わなければ、あなたはライブラリが抽象化している、よりプリミティブなロジックを書かなければならないということを知っておいてください。

unchanged("type");

unchanged("author");

unchanged("created_at");

These lines do just what they say. If the document’s type, author, or created_at fields are changed, they throw an error saying the update is forbidden. Note that these lines make no assumptions about the content of these fields. They merely state that updates must not change the content from one revision of the document to the next.

これらの行はtypeやauthor、created_atの各項目が変更された場合にforbiddenのエラーメッセージを返します。この関数は項目の中身を比較してはいません。単にドキュメントが次のリビジョンに変わるときに変更を許可しないだけです。

if (newDoc.created_at) dateFormat("created_at");

The dateFormat helper makes sure that the date (if one is provided) is in the format that Sofa’s views expect.

dateFormat関数は日付項目をSofaで決めている書式に整えるために使います。

// docs with authors can only be saved by their author

// admin can author anything...

if (!isAdmin(userCtx) && newDoc.author && newDoc.author != userCtx.name) {

unauthorized("Only "+newDoc.author+" may edit this document.");

}

If the person saving the document is an admin, let the edit proceed. Otherwise, make certain that the author and the person saving the document are the same. This ensures that authors may edit only their own posts.

ユーザーがadminであれば、どのドキュメントに対しても常に更新を保存することができます。admin以外のユーザーは自分の記事のみ保存が可能です。このコードで記事の著者が常に一致していることを確認しています。

// authors and admins can always delete if (newDoc._deleted) return true;

The next block of code will check the validity of various types of documents. However, deletions will normally not be valid according to those specifications, because their content is just _deleted: true, so we short-circut the validation function here.

その次のコードでは、ドキュメントの種類について確認しています。ただ、削除処理の場合は以降のバリデーション処理は不要であるため、すぐにtrueを返すようにしています。_deleted: trueであることがわかれば、他はなにも確認しなくてよいためです。

if (newDoc.type == 'post') {

require("created_at", "author", "body", "html", "format", "title", "slug");

assert(newDoc.slug == newDoc._id, "Post slugs must be used as the _id.")

}

}

Finally, we have the validation for the actual post document itself. Here we require the fields that are particular to the post document. Because we’ve validated that they are present, we can count on them in views and user interface code.

最後に、ドキュメントの投稿内容について確認しています。ここでは指定した項目が全て入力されているかを確認しています。項目が揃っていることを確認することで、viewのコードやユーザーインターフェースのコードで確実に項目への処理ができることを保証しています。

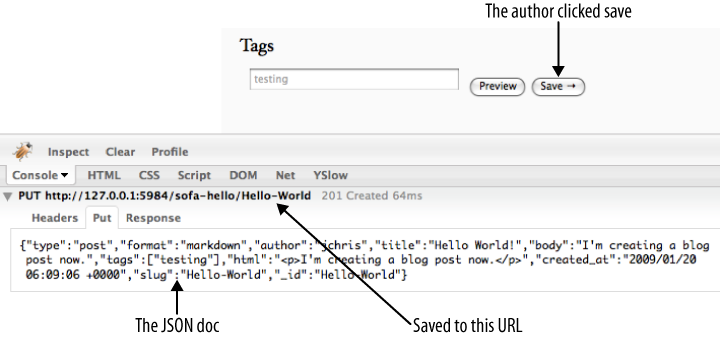

Let’s see how this all works together! Fill out the form with some practice data, and hit “save” to see a success response.

試しに、何か投稿してみましょう!!適当なデータをフォームに入力し、「save」ボタンを押してみてください。

Figure 4, “JSON over HTTP to save the blog post” shows how JavaScript has used HTTP to PUT the document to a URL constructed of the database name plus the document ID. It also shows how the document is just sent as a JSON string in the body of the PUT request. If you were to GET the document URL, you’d see the same set of JSON data, with the addition of the _rev parameter as applied by CouchDB.

図4「JSON形式のドキュメントがHTTPを介してブログ記事として保存される」を見ると、JavaScriptがどのようにしてHTTPを介してドキュメントをURLへ紐付けているのかがわかります。URLは指定したデータベースの名前の次にドキュメントのIDが付くという構造になっています。また、ドキュメントはJSON形式の文字列としてPUTリクエストの内容に含められていることもわかります。ドキュメントのURLに対してGETメソッドを実行すれば、同じJSON形式のデータを取得することができます。そのときには、_revという項目も追加されています。

Figure 4. JSON over HTTP to save the blog post

図4 JSON形式のドキュメントがHTTPを介してブログ記事として保存される

To see the JSON version of the document you’ve saved, you can also browse to it in Futon. Visit http://127.0.0.1:5984/_utils/database.html?blog/_all_docs and you should see a document with an ID corresponding to the one you just saved. Click it to see what Sofa is sending to CouchDB.

JSONのバージョンを知りたい場合はFutonから確認することができます。http://127.0.0.1:5984/_utils/database.html?blog/_all_docsを見れば、ドキュメントの一覧を見ることができます。ドキュメントをクリックすれば、SofaがCouchDBへ送信している内容を見ることができます。

We’ve covered how to design JSON formats for your application, how to enforce those designs with validation functions, and the basics of how documents are saved. In the next chapter, we’ll show how to load documents from CouchDB and display them in the browser.

この章では、JSON形式でアプリケーションにとって最適なドキュメントを設計する方法や、バリデーション関数でドキュメント構造を維持すること、ドキュメントが保存されるときの仕組みをお伝えしました。もしかしたらB木に関する部分まで詳しく知りたかったかもしれませんが、割愛しました。次の章では、CouchDBからドキュメントを読み込んでブラウザーに表示させるところについて紹介していきたいと思います。